Low speed rear-end accidents resulting in claims of neck pain, or whiplash, are a common cause of litigation. As engineering, biomechanics and accident reconstruction experts, we have investigated many of these accidents, as well as the resulting claims of injury, for both plaintiffs and defendants. This article summarizes some of the primary issues encountered in these cases.

A car is stopped for a light when it is unexpectedly rear-ended by a vehicle from behind. It is not a hard impact and there is little or no damage to either vehicle, because the energy absorbing bumpers have protected them. Nevertheless, the passengers of the struck vehicle complain of neck, shoulder and back pain. The next day they allegedly experience even greater pain and visit a medical person who claims that they have been injured. Insurance claim representatives, attorneys, medical, engineering and biomedical experts are then brought in and various conflicting allegations, testimony and opinions are expressed. Do we have a legitimate injury claim on our hands or a situation of fraud? Insurance literature sources claim that 1/3 of such cases are fraudulent; yet, there is a body of research that indicates that low speed impact involving non-damaged vehicles can sometimes cause whiplash.

What are the scientific and medical issues involved? In the following, we shall briefly summarize them and explain what technical information is available to analyze such events.

What is the syndrome called “whiplash”? Here is a brief description. A stopped car is struck by another vehicle from behind; the struck car and torsos of its passengers are thrown forward. However, the heads of the passengers lag behind for a fraction of a second, causing their necks to be hyper-extended (unduly strained as the torso flies forward while the head stays behind). As their torsos rebound against the seat backs, their heads now move forward, but are snapped back again, by their necks, and overshoot the torso, again causing the neck to be hyper-extended. This effect is most severe if the headrests are too low and set too far back, as they are in many cars. The whole occurrence takes less than a second.

Although the person experiencing this situation does not have overt signs of injury, the possible occurrence of soft tissue damage to the overstretched ligaments of the neck has been well documented. This damage may be permanent, causing chronic pain and limitation in neck movement, the full extent of which may not be apparent until about a day after the accident.

Unfortunately, the effects of whiplash are often downplayed, and its sufferer thought to be malingering, on the grounds that injury isn’t visible. In addition, experiments have shown that the forces to the neck during whiplash are not much greater than those occurring during normal activities (e.g. “plopping down into a seat”, “hopping onto a step”, and even “sneezing”). However, unlike whiplash, normal events do not take a person by surprise, so one can instinctively brace the neck muscles in anticipation, and control the force transmitted to the cervical soft tissues. With whiplash, the force to the neck is violent and sudden, and is not filtered through the neck musculature. Hence, those with thinner or weakened necks (i.e. women and those who have had prior neck injury) are more prone to the effects of whiplash, which can occur from an impact to the car as low as 3G’s.

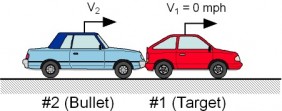

A problem facing investigators of a whiplash case is that the impact velocity of the striking (rear) car is typically not known with certainty, and this value is needed for determining resulting forces. A conservative estimate of the speed can be surmised by using the damage threshold of the cars’ bumpers (because whiplash injury is caused by low speed impacts involving no (or minimal) damage to the bumpers; hence most of the shock is transmitted to the passengers’ necks). Testing has shown the damage threshold of bumpers of many cars to be about 5 mph; thus lash forces to the neck based on a maximum 5 mph impact velocity to the struck car. However, most crash testing involves the car impacting a rigid barrier, which does not yield in any way, rather than a relatively flexible bumper of another car. Hence, the crash testing can be more severe than an actual impact with another car, and can, in fact, be equivalent to the car’s being struck with another car at up to twice the velocity used for the barrier test.

Testing has shown that the maximum loading to a rear-ended car was amplified about two and a half times when it reached the heads of the occupants. The testing also revealed that this occurred about a fourth of a second after impact.

The momentum and loading to cars which are involved in a rear-end impact (of low enough impact velocity so that there is no permanent deformation of the bumpers) can be fairly accurately modeled as a mass-spring system. This enables determination of the loading effects on the cars and heads of the occupants, by input of known quantities (masses of the cars, bumper stiffness, relative velocity between the cars at time of impact).

It is thus possible to determine the likelihood of a claim of whiplash injury being legitimate. Based upon how consistent all incident data is with available research findings and on using as precise a computer model as possible, an engineer with a proper dynamics and biomechanics background can help to determine the viability of a claim.